A young girl helps to move bricks from the kiln to where they are needed at the construction site for Building Tomorrow Ogwari-Odek Primary School.

It’s 2:00 in the afternoon. Children flit about under a mango tree, their feet barely touching the ground as they chase each other in a game of tag, sliding in the mud as they turn a corner because a rain that left no living thing thirsty has just fallen. In the backdrop, a young girl carries a brick in two hands, trailing her father from behind and laughing as he walks towards a classroom block to help mix some cement.

It’s the construction site for the new Building Tomorrow Ogwari-Odek Primary School, and as a young man climbs a ladder to place a brick on what will become the top of a wall of a second grade classroom, he pauses to have a look out over the landscape.

Blanketed in the green of soy beans, maize, and cassava and dotted with cows moving languidly through the endless patchwork of farmers’ fields, there is a certain tranquillity to the place. Tall trees swaying gently, even the breeze seems to breathe calmly over the verdant land.

But this place is not known for peace. Just kilometres away sits the birthplace of the man who would bring almost two decades of civil war to northern Uganda, ushering in an era of wide-scale violence, abduction, and displacement that tore apart communities, livelihoods, and families.

The Lost Generation

It is impossible to understand the significance of the Building Tomorrow Ogwari-Odek Primary School without knowing who this man is and the marks he left on the people and institutions of Northern Uganda.

His name is Joseph Kony, and he was the leader of a rebel group known as the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) that originated in northern Uganda in 1987 amongst Acholi communities who suffered various abuses at the hands of successive Ugandan governments throughout the 1970s and 1980s.[1] While the resistance originally had popular backing, its support waned in the 1990s as the LRA became increasingly violent against civilians, even fellow Acholi—abducting, mutilating, and killing thousands of people in northern Uganda.

“At some point, we all became well aware that the LRA was no longer fighting for the betterment of the people,” a community member told Building Tomorrow. “It was when we saw the abductions of civilians, when it was the civilians who were the ones getting killed.”

The war, while devastating in many respects, had a particularly severe impact upon children and the education system in the North. One of the main reasons was that to boost its numbers, the LRA became notorious for abducting more than 66,000 children to use as child soldiers or sex slaves.[2] In many instances, these children were forced to kill their family members and each other to isolate them and discourage them from defecting, creating an orphan problem that still persists today.

Unfortunately, the easiest and most obvious place to find such children was at school, or on their way there, which discouraged many parents from enrolling or sending their children there. Beyond interrupting access, the violence in the region also affected the quality of schools, as the capacity of local governments to monitor and support schools and deliver Universal Primary Education (UPE) funds was hindered or altogether obstructed.[3]

Moses Okello, Head of the Building Committee for Building Tomorrow Ogwari-Odek Primary School and Community Support Leader for the village of Ogwari, was about 9 years old when the fighting started in 1986.

“Education was affected seriously,” recalls Moses.” Because when pupils were in class and you would get an attack from the rebels, all we could do was run.” Parents, afraid to send their children to school, stopped enrolling them. Teachers, afraid of the violence and suffering from poor delivery of UPE funds and support, stopped teaching.

Around 1994, the government of Uganda finally decided to move people into “protected villages” or internally displaced people (IDP) camps to safeguard them.

“The village was flooded with soldiers,” remembers Moses. “Our village was in a tactical area between the government and rebels so the government decided to collect everyone.”

At the peak of displacement in 2005, there were 242 camps hosting more than 1.8 million IDPs forced from their homes.[4] Most of the people from Ogwari village where the school is being constructed were in the nearest IDP camp to them known as Acet.

While schools existed within the camps, the general consensus is that they were not functioning very well, as basic teaching materials and quality teachers were severely limited, and overcrowding was characteristic.[5]

Thus, an entire generation of displaced people effectively lost out on education while at the camps, and even upon return to their homes, could not make up for this loss.

“The camp really lasted,” Moses explains. “You may find that someone like me went to the camp when he was 13 years old and was resettled in his village when he was already grown. That’s the end of everything. That’s how people dropped out. How are you going to go back to school and be counted amongst children? You just don’t go back.”

The Lasting Effects of War

The war’s effects on the education system lasted. It wasn’t just that education suffered during the war; it’s that education suffered, and continues to suffer, even after the war’s conclusion in 2006. In 2007, a year after the conflict ended, almost 1 million people still remained in IDP camps, as the resettlement process was not a quick one.[6]

“Most of us came back in 2007 and 2008, and some even in 2009,” recalls Moses. “It was difficult to resettle because after all these years, you come back when your home is no longer there. People grew up in the camp. Children were born in the camp.”

More than a decade later, livelihoods have resumed, but the region is still marked by some of the highest dropout rates and lowest learning outcomes in the country.[7] Social investment simply hasn’t caught up to demand, and infrastructure and other educational support in northern districts like that of Omoro are still lacking.

The result of this long wait for education is that some villages like Ogwari decided to build their own community schools to provide at least some education for their children in the meantime.

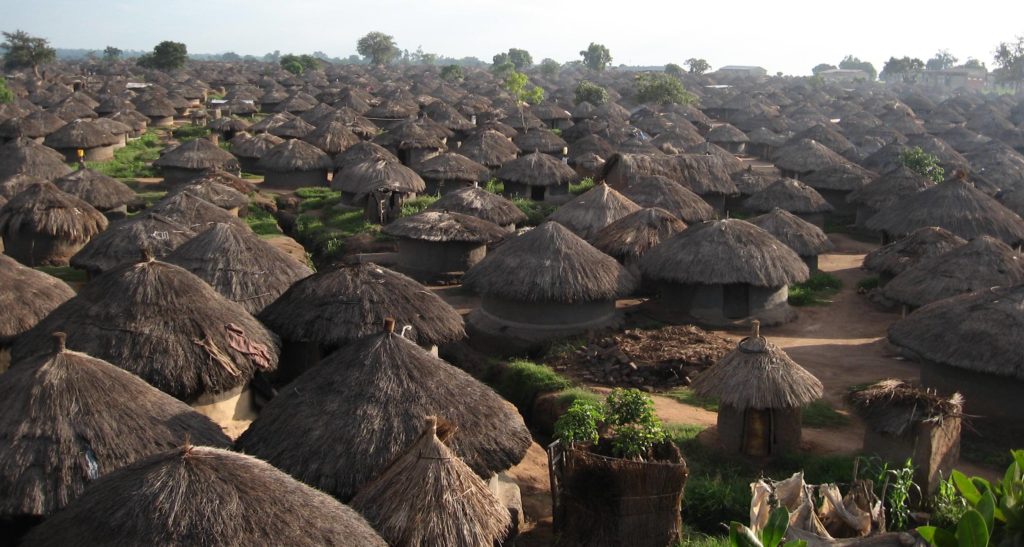

“After returning from the camps,” explains a village elder named Jackson, “the community organized itself, and we built classrooms using mud blocks and grasses and thatch for roofing.”

While well-intended, however, the structure has not proved adequate for accommodating the children, and demand for education is so high that several of the classes even sit outdoors under trees.

The structure simply does not protect from the elements or provide a safe, quality learning space, and as Moses explains, “Any time there is rain, that’s the end of education on that date!”

The temporary grass-roofed structure currently used by the community of Ogwari

Because the temporary thatch structure is not large enough to accommodate everyone, some classes study beneath trees using stones or bricks for seats.

While the gaps in the thatch roof allow in light so that students can see, they prove problematic on rainy days.

While the gaps in the thatch roof allow in light so that students can see, they prove problematic on rainy days.

Lacking desks and other materials, students sit on logs or bricks just like this one. Sitting in such positions for long periods of time is uncomfortable and makes it hard for the students to concentrate on their lessons.

The Next Chapter

The new Building Tomorrow Ogwari-Odek Primary School, however, is changing this story and allowing a new history of hope and opportunity to emerge from a region that has been wrought with so much destruction.

The authors making this new rewriting of the village’s circumstances possible include Richard Awong, the land donor who has given five acres of his farm to ensure that the community’s children have the learning opportunities that he did not. As with Moses, the civil war greatly impacted the livelihood of his own family and his education, and he dropped out in third grade.

“I was unable to pay school fees,” Richard says plainly. “And there were rebels and bullets flying up and down the area.”

But the new school offers a chance to give his children a better life and access the education that he could not.

“The war affected me personally,” says Richard, “and at the same time, it has affected my children. I have put my hopes on my three children going to school, and that is why I donated the land. I have a vision for education in this area. Without education, there can be no development.”

As with many parents, the school represents for Richard a chance to write a new history for his family and community, marked not by destruction and despair but rather opportunity and strength.

“I have hope now that the school is here,” says Richard. “Now, my children can be doctors or whatever they want to be.”

The Building Tomorrow Ogwari-Odek Primary School is one of 81 schools currently built or under construction by Building Tomorrow. To find out more about our construction model and efforts to bring new primary schools to underserved communities in Uganda, click here.

[1] Q&A on Joseph Kony and the Lord’s Resistance Army. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2012/03/21/qa-joseph-kony-and-lords-resistance-army

[2] The World Bank. (2006). World Development Report 2007 (p. 182). Washington, D.C.: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank.

[3] Bird, Kate, Kate Higgins, and Andy McKay. (2011). Education and resilience in conflict and insecurity-affected Northern Uganda (p. 65, 68-69). Working Paper. Chronic Poverty Research Centre: London, UK.

[4] UNHCR. (2007). Closure of camps starts in Northern Uganda as IDPs return home. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/news/briefing/2007/9/46e66ea52/closure-camps-starts-northern-uganda-idps-return-home.html

[5] Annan, Jeannie, Moriah Brier, and Filder Aryemo. (2009). From ‘Rebel’ to ‘Returnee’: Daily Life and Reintegration for Young Soldiers in Northern Uganda. Journal ofAdolescent Research, 24.6.

[6] UNHCR. (2007). Closure of camps starts in Northern Uganda as IDPs return home. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/news/briefing/2007/9/46e66ea52/closure-camps-starts-northern-uganda-idps-return-home.html

[7] Mwesigwa, A. (2015). Uganda’s success in universal primary education falling apart. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2015/apr/23/uganda-success-universal-primary-education-falling-apart-upe

Follow Us on Social Media