Curse. Ghost. Ugly.

Would you ever use these names to refer to a child?

Probably not. But if you’re a child with albinism in Uganda, chances are you’ve been referred to in this way, and not just once.

Albinism—a group of inherited conditions including absence of pigment in the skin, hair, and eyes—carries with it some degree of social and physical challenge no matter where you are in the world. But in Africa, it’s a whole new ball game.

Because in Africa, most people have dark pigmentation in their skin, making those with albinism extremely visibly different from their families and communities without albinism. They deal with the incongruous reality of “being black in white skin.” They feel different even when they’re the same.

In Uganda particularly, albinism is widespread.[1] And so are cultural myths and stigmatization surrounding the condition. In general, people with albinism are feared and looked upon as bad luck while their body parts are simultaneously and paradoxically valued and sought after for their good luck.

The result of this discordant belief system is that people with albinism are ostracized and often bullied for their differences, yet pursued for their body parts that are believed by some to bring success, wealth, or other positive outcomes. Such deep-rooted superstitions have resulted in the harm and sometimes killing of children, especially in the Busoga region, when their hair, fingers, or limbs are forcibly taken to use in witchcraft-related rituals and charms.

If they are thick-skinned, so to speak, and can withstand the prejudice, stigma, antagonism, rejection, and other adverse social impacts brought about by their condition, they still have to deal with the physical impacts such as extreme sensitivity to the sun that results in sunburn and blisters and poor vision that affects most people with albinism.

Abandoned but Not Alone

9-year-old Jemba in Kiboga District is one such boy making his way through the world with albinism who has been brought back to school and given the critical support that he needs, thanks to intervention by our Building Tomorrow Fellows.

Viewed as a punishment from God and abandoned by both his father and mother when he was just one year old, Jemba has been in the care of his grandmother for as long as he can remember.

As Building Tomorrow Fellow Robert Lumu who works with Jemba’s school explains, “Basically, in Uganda, and not even just Uganda but all of East Africa, people believe albino children are cursed. After giving birth to him, his parents abandoned him. They thought he cursed the family so they would take him to the field and just try to leave him there. He doesn’t’ even know what his father and mother look like, just that they exist.”

That’s where Robert and another nearby Building Tomorrow Fellow, Gloria Kunihira, first found him, with his grandma sitting at home.

Due not just to social stigmatization but the physical challenges he faced related to his condition, that is where Jemba remained each day instead of in school.

“I feel like there is a fire burning inside my skin,” says Jemba of the sunlight that he has to face in a country where sunny days dominate the calendar year. His eyesight, too, causes him trouble.

To get Jemba back to school, therefore, the Fellows knew they would be fighting not just the negative social stigma attached to his condition but would also need to seek outside support to address his physical limitations and barriers to learning.

Pushing for Partnership

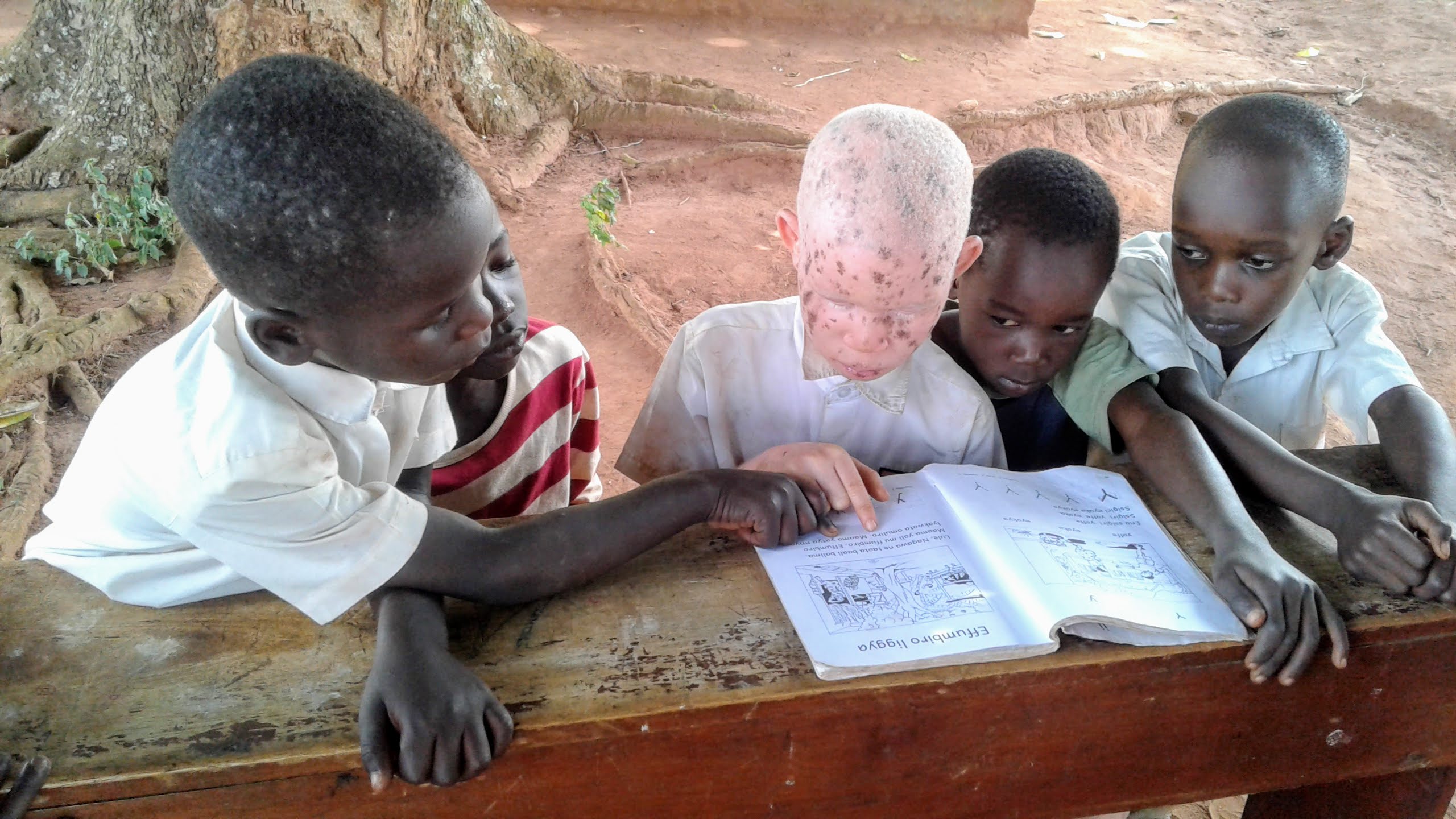

The first step was getting Jemba enrolled in class and getting the others to accept him as a peer.

“The first days were a bit challenging,” recalls Robert. “Other learners didn’t want to associate with him. They wouldn’t even sit at the same desk with him. But as the teachers and I kept on encouraging them to associate with him, these days he is okay, and you can even find them playing together with him.”

While the acceptance by Jemba’s peers was a big win, however, Jemba still struggled to learn in class due to his eyesight.

“Studying was difficult because he could not see what was being taught in class well” explains Robert. “And writing was also a challenge, as he needed a magnifying glass just to be able to see within the margins of his book.”

That’s when it hit home that more had to be done, and the Fellows reached out to the Uganda Albinos Association in Kampala for guidance and support. The Association, which seeks to protect and promote the right of the albino community which has been historically demonized and marginalized throughout East Africa, was very responsive. It started supplying Jemba with sunscreen lotions for his face and body along with a pair of sunglasses, a service it promises to deliver for the rest of his life. Moreover, it committed to do an eye exam in order to provide a concrete solution to Jemba’s eyesight problems.

A Child Like Any Other

This news was music to Jemba’s grandmother’s ears. “He’s a child like any other,” she says. And now he is beginning to access the resources and form the relationships that he needs to succeed.

Instead of sitting at home, he’s out making new friends and learning new things. “He even does comedies at school,” says Robert. “You’ll find all the children seated around him when he’s telling them funny stories. And he’s getting more friends and used to other people who aren’t like him. I think we have really restored his hopes and self-esteem.”

He is finally a part of a group and starting to learn just like everyone else, and this is due in no small part to the relentless determination of teachers’ efforts to integrate him into the classroom.

“What I like most at this school,” says a happy Jemba, “are the good teachers who try as much as possible to see that I fit in the school community and enjoy the school like any other child. I also like my classmates because they are good to me, although the isolated me at first when I joined the school and feared me because of my skin colour. Now I have two best friends.”

Jemba is now enjoying first grade at Kanziira Islamic Primary School and showing that a child is a child no matter what colour and can learn, too.

“At least they know now,” says Robert with relief. “The child is not a curse. He just has different skin.”

Robert and Gloria are part of a group of 100 Building Tomorrow Fellows currently mobilizing resources and bringing out-of-school children back to class in rural communities through our Thriving Schools Program. Robert, Gloria and all of our Building Tomorrow’s efforts are supported by Educate A Child with special support for inclusive education from the Joseph P. Kennedy Foundation. To find out more about our Thriving Schools Program and how it has brought more than 52,000 children like Jemba back to school, click here.

[1] Bradbury-Jones C, Ogik P, Betts J, Taylor J, Lund P (2018) Beliefs about people with albinism in Uganda: A qualitative study using the Common-Sense Model. PLoS ONE 13(10): e0205774. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205774

Follow Us on Social Media